Never Mind the Bollocks: a single sharp, strong and effective blow

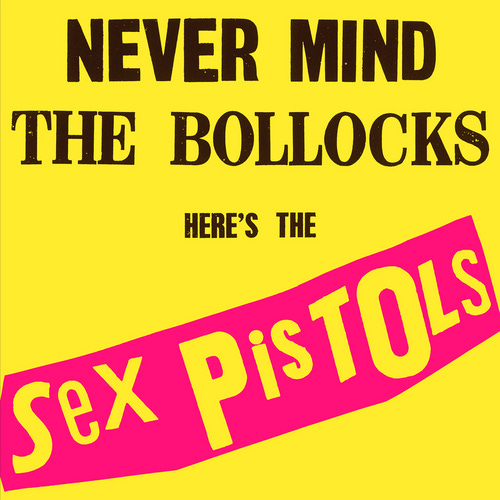

In my top 5 of things I would do when I have my time machine, without a doubt would be entering a record store in the late ’70s to search among the bins for that screaming yellow with magenta typography that no designer would defend again without irony. And clearly, the next scene would be approaching the counter outraged and starting a fight with the clerk because they don’t have the best album in history. But back in my time one has to ask: how can it be that a unique album —an album without a sequel, without a second part, without later stumbles— continues to have such a disproportionate weight in musical culture? How can it be that the Sex Pistols, with a single official recording before disintegrating, left such a deep mold that still organizes entire discussions, aesthetics, and vocations? The quick answer, the one you say when you don’t want to get technical, is that the myth weighs more when it doesn’t wear out. But the truth is more complex, and also more interesting: Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols survives because it is one of the few albums in the history of rock that sounds exactly like its context. And few times has a context been so unstable, so furious, so willing to be pushed to the edge of collapse.

If you like my work, support me on Ko-Fi.

To understand why this unique album works as a generational document, you have to go back to that dim United Kingdom in the mid-seventies. The Sex Pistols did not appear out of nowhere: they sprouted from the kind of hopelessness that only appears when a country is certain that it no longer knows where it is going. In London, strikes paralyzed transportation, blackouts left entire cities in darkness, and youth unemployment set records that seemed deliberately humiliating. Symphonic rock sounded like the soundtrack of an empire that did not want to accept its aging. The big bands were so big that they flew over their roots without recognizing them. And the Sex Pistols arrived right in that gap, not as an organized alternative but as a violent interruption: the band that demanded nothing because they had nothing to demand, because the hope of needing something had become disconnected from reality.

In that murky landscape, Malcolm McLaren understood something before anyone else: discontent didn’t need a spokesperson, but an amplifier. His idea of managing the Pistols was closer to directing a conceptual piece than to managing a band. John Lydon, with his nasal voice and his attitude of perpetual mockery, made every song sound like an accusation; Steve Jones had the ability to play riffs that seemed like a rusty chainsaw sending splinters flying everywhere, but that were as solid as most classic rock guitarists of the time; Paul Cook contributed the pulse that kept everything standing, aligned but vertiginous; although Glen Matlock’s contribution to the recording was small, the spirit of his bass line resonates, guides, and elevates each song; and then there was Sid Vicious, whose musical participation was minimal but whose aesthetic presence completed the puzzle. It’s not that Sid played: Sid represented. And in that visually obsessive world, that was enough to write half the band’s story.

Sometimes it is said that Never Mind the Bollocks is a badly recorded, dirty, primitive album. In reality, it is exactly the opposite. It is a surprisingly well-produced album: compact, wide, almost luxurious compared to later punk standards. When Steve Jones recorded layer upon layer of guitars, he wasn’t building noise or melody but volume, an even wall that gives the sensation of listening to something coming right at you. The songs work because they are made with the energy of a demo and the structure of a traditional rock album. They are eleven destructive and fast bombs, but they also don’t sound as if they had been assembled in a hurry in a basement.

The lyrics of Never Mind the Bollocks work as a brutal X-ray of a country that seemed not only worn out, but cynically resigned to its own deterioration. Anarchy in the U.K. does not propose a political project: it captures the feeling that no institution represented the interests of youth. There are no manifestos or programs; what there is is a cornered lyrical self, caught between fury and apathy. God Save the Queen, for its part, articulates a contrast that the British press considered sacrilegious: marginalized youth faced with a state apparatus celebrating the silver jubilee of Elizabeth II while working-class neighborhoods accumulated unemployment, deteriorated housing, and a declining public education. The most striking thing, reviewed today, is that these songs do not align with a specific ideology: they function more as a cultural diagnosis of a generation that, instead of claiming a place within the system, chose to expose its rot.

That diagnosis became especially resonant because the United Kingdom of the mid-seventies was a country that had lost confidence in its own narrative. Strikes, inflation, the famous Winter of Discontent, political violence in Northern Ireland and the widespread feeling that the future had already been canceled pushed young people toward a form of expression that rejected both political moderation and musical virtuosity. The lyrics of the Sex Pistols were not sophisticated nor pretended to be: they were written so that any kid without musical studies could feel that he also had the right to say something. That gesture —that symbolic permission to participate— was decisive. In a context where progressive rock had become synonymous with technical excellence and a certain elitist distance, punk returned music to street urgency, to anger without diplomatic translation, to an authenticity that was confused with improvisation. The key is that the songs not only represented precariousness: they sounded like precariousness. And that aesthetic coherence was political in itself.

The global expansion of punk —and, in particular, of the street spirit encapsulated in Never Mind the Bollocks— has to do with how that British anger found equivalents in very different realities. In the United States, Australia, Latin America or continental Europe, youth recognized in the album an energy that transcended its geographic origin. The album became an exportable language because the frustration it expressed had correlates in any city marked by unemployment, inequality, or the sensation that the future was being decided by others. Not all countries had a queen who displayed her power and riches from the arrogant throne of the gods, but they had a political class that demanded your democratic vote with the same impunity.

Moreover, the youth culture of the late seventies was already crossed by faster circuits of exchange —import record stores, music magazines, late-night radio programs— that allowed a gesture as local as the fury of London’s working-class neighborhoods to become a transnational phenomenon. That punk became an archetype —an aesthetic, a sound, a posture— has to do with the fact that in Never Mind the Bollocks there is no sociological portrait, but a basic, visceral, and recognizable emotion, almost universal: the imminent desire to disobey. That is why the album continues to resonate today: because each era generates new forms of conformism, and each generation needs to remind itself that the possibility of breaking the mold exists.

And of course, scandal also plays its role. Censorship, alarmist headlines, the famous boat on the Thames, radio stations that refused to play God Save the Queen… all that was fuel. There is no myth without an antagonist, and the Sex Pistols had the entire establishment as an antagonist. The press, the police, the BBC, the parents who saw how the status quo they helped build crumbled in their living room, sat at their table and dined with them with that youthful fire they had lost —all contributed to the same scenery: that of a group that was dangerous because it said something that needed to be silenced. In 1977, being offensive still meant something. And the Sex Pistols knew it.

But the most disturbing part of their influence is not the noise they made while they existed, but the buzzing they left when they fell apart. A band that breaks up too early always leaves a romantic trail. But a band that breaks up after a single album leaves the illusion of perfection. There is no minor album to rescue, no slowdown, no decay. There is no weak phase. The catalog has no curves: it is a solitary and sharp peak. And that makes the Sex Pistols an almost clinical case of perfect failure.

And what became of them afterward? Because the question is inevitable when the story ends so abruptly.

John Lydon carried on with PiL, a project as experimental as it was stubborn, that functioned as the opposite of everything the Sex Pistols had been. If punk was immediacy, PiL was insistence. And today, while the Sex Pistols brand is reactivated with Frank Carter as frontman, Lydon continues touring with his band as someone who keeps an open argument with his own biography.

Steve Jones took a different path: between rehabilitation, moving to Los Angeles and intermittent projects, he ended up becoming a cult radio figure. From his program Jonesy’s Jukebox, he interviewed half the rock world with the naturalness of someone who has nothing to prove. Neurotic Outsiders was an interesting and short-lived supergroup of the ’90s and I enjoyed his cameos in Californication in the ’00s.

Paul Cook, the most stable of the group, continued playing in multiple projects, including The Professionals. He was, in many ways, the one who maintained the most pragmatic relationship with his past: music as a craft, not as a relic.

Glen Matlock, after his early departure from the Sex Pistols, played in bands like The Rich Kids and collaborated intermittently with punk and power pop figures, always maintaining a craft closer to that of a craftsman than a chaotic icon. Over the years, he became a sought-after and respected bassist, someone who never needed the persona to sustain his career.

Sid Vicious had no future to tell. His story —jail, Nancy Spungen, heroin— is more tragic myth than biography. It is impossible to talk about his end without feeling that the character ended up devouring the musician, and that his death froze a narrative he himself could no longer sustain.

And Malcolm McLaren continued being McLaren: designer, performer, theorist of chaos. His later projects mixed fashion, music, conceptual art, and self-promotion with the same theatrical intensity with which he had directed the Sex Pistols. His death in 2010 closed the last direct voice of that choreography he had sustained from behind the stage.

But the question that really matters is not what they did afterward. It is what the album did afterward. And there the answer is simple: it organized punk as an aesthetic, a gesture, and a method. It taught that anyone could pick up a guitar. That energy was enough. That a band could be a short but infinite project. The influence of the Sex Pistols was more pedagogical than musical: more than teaching what to play, they taught that you could play. That music was not a private club.

That is why bands like Bad Religion, Nirvana, Green Day, Rancid, even Rage Against the Machine —each in their own way— owe them a foundational gesture: permission. The license not to be virtuosic, not to fit in, to use music as a weapon or as a joke, or both at the same time. Yes, The Clash and Ramones among others were also cornerstones in history, but here we are talking about a single sharp, strong and effective blow.

Today, Never Mind The Bollocks Here’s The Sex Pistols occupies a strange place: it is a museum piece that still breathes. It is in reissued vinyls, in lists of the top hundred albums, in tattoos, in T-shirts sold in stores that would have called security if a member of the band had approached their window. It is a brand, a memory, a noise that does not fade. And at the same time, it is a living piece, because it continues provoking that uncomfortable mix of tension and excitement when Pretty Vacant starts playing.

And if I go back to the time machine to that era, the romanticization dies when it crashes into that reality. If you feel the anguish of the streets then the album has another feeling, and the initial question —how can a single album continue weighing so much— no longer needs an answer. Or rather: the answer is in the experience itself of listening to it again. In that electric instant when the guitar comes in and one feels, almost without understanding why, that the world tilts a few degrees.

With a single album, the Sex Pistols achieved something that most bands don’t achieve even with twenty: becoming an inevitable reference. A kind of eternal match that each generation lights again when it needs to remember that sometimes music —good music— begins when someone decides they are no longer willing to listen to more of the same.

And that, after all, continues being the most honest definition of punk.

Thanks for reading.

☕ If you like my work, you can buy me a coffee on Ko-fi.

I bought Bollocks soon after it was released and smuggled it into my bedroom so my parents didn’t catch me. I nervously put the record on my turntable but the hole in the middle was too small to fit over the doohickey in the middle of the platter. I took a pencil and worked at making the hole bigger but I only succeeded in making it lopsided. Whenever I played it the record wobbled, which was probably appropriate. This album has been and always will be the greatest recording for rebellious teens and 62 year olds.

It’s important to state. That with all the censorship and being banned from the airwaves. Never Mind The Bollocks still debuted at #1 on the uk charts. Although there was a lot of fuckery by the BBC and their record label EMI.

Also interestingly Malcolm and his partner Vivienne were trying to find a sexy bad boy frontman for the band and somone had recommended Sid.

But due to some mixup it was Johnny who showed up to the rehearsal. And also the one who could write lyrics and songs.

After Johnny quit.

Malcolm tried carrying on the band the way he had envisioned wo the Sid as front man. Which led to the ill fated trip to the carribean? Or somewhere where they filmed The Great Rock and Roll Swindle.

And Sid’s cover of My Way.

Johnny kept begging Malcolm to keep Sid away from the heroin and keep an eye on him. But alas. The human incubus that was Malcolm. Gave no fucks and whored Sod out to the devil and let him feed his addictions that led to the unexplained deaths? Murders? Suicides? Of Sid and Nancy.